Don't throw stones at me

Don't tell anybody

Trouble finds me

All the noise of this

Has made me lose my belief

I'm going back to my roots

[Imagine Dragons - "Roots"]

A little over a year ago, I began the process of breaking away from Mormonism. I did not want it to happen, and I fought desperately against the growing dissonance. For months, I poured an exhausting amount of energy into seeking authentic grounds to stay.

But I eventually gave way.

At the risk of sounding too self-serious, the ordeal has been rather traumatic. I have cycled through the stages of grief, many times, and spent a majority of my free thoughts these past 15 months sifting through the wreckage of lost faith and hoping — really hoping — to find something salvageable in the fallout.

This post is the start of a vulnerable and somewhat uncertain journey for me. I’ve felt purpose in looking back and re-evaluating my life thus far, carefully retracing my steps on the path of faith, and then writing about it: where seeds of faith were planted, how (and why) they took root as well as they did, and finally, how I got here.

It will probably take me several posts to work my way through this project, and that will probably take a little while. But I seem to have time. Ideally, I’ll uncover something as lofty as meaning through this bit of candid reflection. And if not meaning, I’d probably settle for something close to understanding.

Mom and Dad

Years before I came into the picture, Mom and Dad began their own separate journeys.

Mom grew up the oldest of two children and describes having been raised mostly in the Protestant faith, though sometimes Methodist and sometimes Presbyterian (depending on how Grandma liked the minister and his politics). Mom joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (“LDS” or ”Mormons” are common shorthand references, though they're now rather controversial in the faith) after her first year of college in Boston. Mom’s faith journey is her own story, and I’ll leave it to her to tell it. I'll note, though, that she once told me that as she learned the faith's tenants, she felt like she was simply remembering things she'd always known.

Mom transferred to Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, after her freshman year, and eventually helped bring her parents (Grandma and Grandpa Feickert) into the faith as well. They were “sealed” together as a family in the Washington, D.C. Temple in August 1975. Grandma and Grandpa Feickert both held to that faith through to the end of their lives.

Dad, meanwhile, was an Idaho boy raised in the faith, the 7th of 9 children. The Clark Mormon roots extend back to Dad’s great, great, great grandfather Ezra Thompson Clark — a polygamous contemporary of Joseph Smith.

After Dad’s first year at Ricks College in Rexburg, Idaho (now BYU Idaho), he served a two year mission for the church, preaching the gospel in South America. Dad used to say that he had a reputation in his mission for being a "flecha derecha" (straight arrow) because of his insistence on following mission rules (at least a few of his mission companions have confirmed this). The stories Dad later told me of his mission took on a larger than life quality as I grew up and helped root me in a particular view of spirituality — one primarily centered on obedience.

His stories were also not so subtle signals for the kind of missionary (and person) I should aspire to be.

After his mission, Dad finished an associate's degree at Ricks College and eventually found his way to BYU, where he met Mom. The way Dad has told it, they went to see "Our Town" on their first date and held hands. Dad wrote once of coming home from the date and asking his roommate to be his best man, so the date apparently went well. Mom and Dad were engaged a few weeks later — a timeline that is not uncommon at BYU — and married a few months after that. Notably, they apparently kissed for the first time only at the conclusion of the marriage ceremony (a feat of restraint that Dad had pushed for, both to make sure he was morally clean and that his relationship with Mom was based on something more than physical affection).

I followed a little over a year later.

Upstate New York

We spent all of my formative years — at least all those I can remember — in upstate New York. Dad tried his hand early on (and apparently failed) as an NFIB salesman, but my earliest memories of him are as a newspaper reporter for The Palladium Times in Oswego, NY.

By the time I was in first grade, Dad had transferred to The Evening Telegram in Herkimer, NY, and Mom and Dad eventually bought a home in nearby Ilion, NY. They lived there 15 years.

Dad would change newspapers one more time while we lived there before falling out of the business entirely (until a more limited return much later in Utah). He then tried his hand (again) at sales and various other jobs while we lived there, but nothing stuck for more than a few years. In between there were several stretches of unemployment, sometimes long stretches, that always felt ill-timed and caused significant financial and emotional strain. As a child and later a teenager, I never fully grasped the extent of that strain, but I felt enough of it that those times still felt traumatic.

Despite their persistent financial difficulties, Mom and Dad eventually had 9 children. They probably didn't intend on 9 (I do have a set of fraternal triplets among my siblings), but having children was itself an act of faith, since the church teachings prevalent at the time were against a married couple "curtail[ing] the birth of their children." Some prominent leaders even outright stigmatized the use of birth control as a “gross wickedness.”

Mom also faithfully stayed at home to raise us kids, at least until my late teens. This, too, was a faithful imperative, since stay-at-home motherhood was (and still is) considered a woman's highest calling. These notions are less heavily emphasized now (one of the church's current apostles has a wife who worked as a lawyer while they raised their daughter). But it's still a thing, and it would later heavily impact the trajectory of my own marriage and family.

When Mom ventured back to school and a new career in my late teens, my youngest brother was only a few months old. I thought I remembered hearing rumblings that some viewed Mom’s choice as controversial and lacking faith. Mom doesn’t remember that, though. In fact, she’s told me a few times that Dad mostly seemed to be relieved by her decision.

Church Service

Meanwhile, I don’t remember a time when Dad wasn’t rotating between some local or regional leadership position in the faith. This included several years as our local congregation’s first branch president (the congregation was never large enough to become a “ward”). As best I could tell, Dad’s leadership style and sermons ("talks") were an extension of the straight arrow he'd tried to be since his mission. I sometimes accompanied him when he would visit single women in the congregation (to avoid the appearance of impropriety).

Mom’s service was less prominent, almost necessarily so in a church with all male priesthood, but she also took turns as the local Relief Society and Primary president (the church’s women’s and children’s organizations, respectively), as well as in the regional (stake) primary presidency. Mom’s sermons and testimonies were less frequent, but when she spoke, she conveyed no less conviction than Dad — though she always felt a bit edgier, by comparison.

Childhood

My childhood is filled with scores of happy memories: baseball cards, Little League, Sunday dinners, no bake cookies, driveway basketball, Nintendo, Twilight Zone marathons, Christmas, and late night runs for donuts and chocolate milk (just to name a handful). Dad taught me to ride a bike and played with me — Wiffle ball, home run derby, and board games. We also rooted for the Chicago Cubs and BYU football together. Mom, meanwhile, made specialized birthday cakes, bandaged skinned knees, and knelt with me for nightly "personal" prayers. She was the one to wish me "sweet dreams" as she turned off my bedroom light each night, and hers was the side of the bed I ran to when I had nightmares. Mom was also the parent I approached for sleepovers and all other requests (her default was "yes" absent a compelling reason; Dad's default was always "no" absent a compelling reason). I alternately fought and collaborated with my closest brother Nathan in regular intervals, and we built forts, collected aluminum cans, and delivered newspapers in tandem.

In all, I had a loving family, and I took that security blissfully for granted.

One of my first memories of spiritual experiences came when I was a first grader in Mohawk, NY. My parents were watching the older version of Clash of the Titans in the living room downstairs, and I somehow caught the part of the movie showing Medusa, whose snakes for hair looked so menacing. The image terrified me.

I was sent upstairs to bed at some point afterward, but I couldn’t get that horrible picture out of my mind. I was so frightened.

I don’t remember exactly how my parents found out how afraid I was, but they did. And then Dad dressed up and gave me a priesthood blessing (he always dressed up for blessings), surely something along the lines of not being afraid and finding sleep.

In my memory, immediately after the blessing, I could no longer see the image of Medusa’s head in my mind. Instead, every time I thought of what I’d seen, I could only picture the head of the Statue of Liberty, and that just wasn’t scary at all.

The image never troubled me any further.

I have revisited that memory over and over in the last year or so, especially early on as I tried desperately to stem my loss of faith. Mom doesn’t remember the incident, and Dad is now gone. Reluctantly, I’ve had to concede that memories — especially from that long ago and that far back into childhood — can be fickle things, suggestible, malleable, sometimes unreliable. And yet the relief I felt as a little boy feels as vivid and real as any memory I’ve ever had. So I’m inclined to treat the memory gently, for whatever it's worth.

In The World But Not Of The World

Growing up, my home seemed to be different from others I knew of, even sometimes among those in the church. Keeping the sabbath day holy meant the three hours of morning church, of course, but also no sports, no shopping, and no video games (which I didn’t get to have until I was older anyway). Sometimes it also meant no television and no watching sports, though Mom and Dad were lax on this one more often than not. [Mom has relayed that Dad had a particular weakness, apparently from the beginning of their marriage, for reading the sports page on Sundays. Maybe it was just a “slippery slope” to eventually tolerating football (and other television) on Sundays].

Coffee, tea (except herbal), alcohol, and even caffeinated sodas (part of a prominent interpretation of the faith’s health code — the “Word of Wisdom”) were unthinkable contraband in our home, as were playing (“face”) cards and "R" rated movies. Swear words likewise weren't tolerated (nor many of their substitutes), so there was a mixture of bemusement and horror on the few occasions Mom got angry enough to let a few loose.

As for music, Dad and I battled over whether I could even listen to the local soft rock radio station (too worldly), though he eventually caved and let me have a stereo/CD player for Christmas. He even bought me a few Richard Marx CDs to go with it, which felt like a major shift.

Also, no dating before I was 16, though this was more a theoretical boundary, since I hardly had any female's attention before then anyway.

I think I mostly tried to be a good boy growing up, and I had my moments. But I was never close to a model child. In fact, the more I sit here thinking about it, the more mischievous behavior bubbles to the surface of my memories, all but clouding out any notion that I was ever very good.

For instance, for a stretch of years in grade school, I had a recurrent problem stealing money from my parents and grandparents. After my first few offenses, Dad once hauled me over to the local police station, where an officer explained what would happen (jail) if I kept to my life of crime. That was scary, but the effect only lasted a little while. More offenses followed in 3rd or 4th grade, and I remember once genuinely fearing Mom would carry through with her threat to throw me out of the house (I packed my bag very slowly before, hours later, she frustratedly allowed me to stay). I also had to spend a few weeks in the summer of 1987 working off some restitution to Grandma Feickert.

A lot of what I did growing up makes me wince now, mostly in those instances where my actions caused hurt or pain to others. For a variety of reasons, I won’t catalogue my misdeeds here, but they were legion. [This probably explains why I’m the hopelessly “soft” parent and Michelle the frustrated disciplinarian — I remember all too well the myriad mistakes of my youth.]

Family Home Evening and Scripture Study

We held weekly family home evenings (church mandated family nights) on Mondays that included songs and games and treats, and supposedly some semblance of gospel instruction. When I was very young, we'd also sometimes make audio cassette tapes for my grandparents.

I have warm memories of family home evenings in my earliest years; far fewer as I got older. The colder feelings may largely reflect the years of general friction I felt with Dad as I grew into a teenager. In those years, I mostly remember Dad conducting the meetings, and they seemed to be little more than a forum for chastisement and criticism, as well as reviewing the weekly family schedule.

The same for our sporadic family scripture study. For Dad, this meant militantly marching the family through chapters of the Book of Mormon (Mom is strangely hard to place in any of these memories). He would mercilessly correct mispronunciations or missed words along the way — a practice that seemed traumatizing for any who had difficulties with reading. In my memory, these rituals turned acrimonious more often than not, and felt like a breeding ground for resentment and hard feelings. I began to really hate these efforts.

With hindsight now, and my own portfolio of well-intended parenting failures, I see that Dad was just doing what he knew. To him, these practices were commandments, and he was faithfully trying to check those boxes. He didn’t seem to know how to peaceably negotiate defiance or defuse tension among children. He may not have been self-aware enough to know how crushing some of his responses could be. And he probably didn’t feel like he had any other other faithful choice than to move forward. So perhaps he simply accepted the discord as an unfortunate (but unavoidable) byproduct of doing his duty.

Years later, I would face similar issues with my own budding teenagers. And I realized that maybe Dad felt the way I often did: helpless. Helpless and hoping the promised blessings of obedience would make up for any lingering psychological damage.

Junior High and High School

The transition from grade school to junior high was rough for me. I dealt with a few bullies and some teasing, though I don’t remember the Mormon thing having anything to do with that. I also quickly became aware how much shabbier my clothes seemed compared to everyone else’s (or at least those I began comparing myself to). Most days I also skipped lunch, preferring hunger to the dread of having to audibly respond "free lunch" (in front of classmates) to the lady with the clipboard in the cafeteria line.

Beyond that, the almost nonchalance with which I’d excelled in grade school didn’t translate so well to junior high, and I had some trouble forcing myself to be diligent with schoolwork. I also felt like I had few friends at school, since I was a bit shy, and the kids I was closest to were from church and mostly lived in neighboring towns.

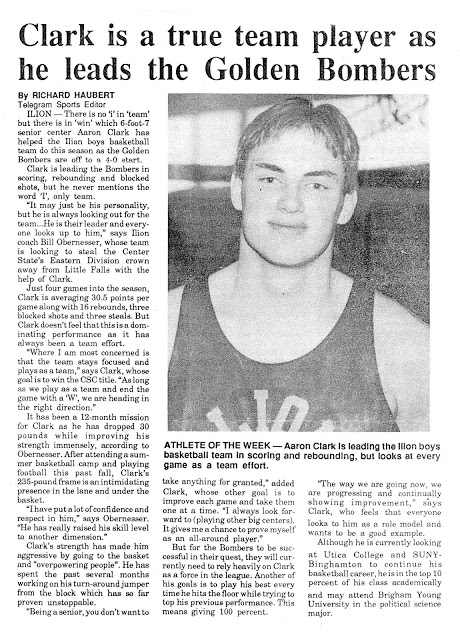

All of that gradually seemed to ease as I moved into 8th and then 9th grade. By then, I‘d grown to be about 6’ 5”, and played football, basketball, and baseball. Baseball would fade away, and a couple of knee surgeries in successive years kept me off the football field in 10th and 11th grade. But I found success and some notoriety with basketball, which left me just popular enough to get onto the student council.

I was still rather introverted, though with some shades of Dad's personality traits. So I could be shy but still perfectly comfortable in (even craving) the spotlight; overly confident and sarcastic among those I knew well, but uncomfortable and insecure talking to new people. I could be quiet, but I still reveled in argument (and often stuck my foot in my mouth).

As a teenager, I also had early morning seminary (a theology class held at the church each morning before school) with other youth in the branch. That was a difficulty all its own. I faithfully attended all four years, though that may have been more my parents’ doing than mine (it was never presented as optional). In my own way, I unwittingly terrorized most of my early morning seminary teachers — taking out on them the fact that I had to be up so early for spiritual lessons [my first seminary report card included the searing observation, “Caustic remarks and unresponsive answers may affect grade.” That probably could have summed up my first three years.]. More than once, I remember teachers trying to gently help me be more welcoming and mindful of others in the class — a deficiency I couldn't really see in the moment. When I would learn that my actions had made others feel uncomfortable or unwelcome, I always felt terrible.

It was in those high school years that it felt like being Mormon became a core part of my identity. The Sunday restrictions, the no swearing, and the Word of Wisdom stuff started to define who I was. Mostly for the better, I think.

There were earnest questions and some good natured teasing from peers in those years. The notion of 3-hours of church each Sunday blew people’s minds, and I remember one classmate astutely questioning why I had no issues eating chocolate, if caffeine really was taboo.

In one of my less pleasant memories, I remember feeling cornered by several classmates in a study hall and needled about the foolishness of some beliefs related to chastity and the Word of Wisdom.

|

| Senior Photo |

I wish I could say that I always responded to questions or teasing meekly, but I could be condescending and self-righteous when cornered (though, again, lacking the self-awareness to realize those were things and they could sour one's effort to be good). Part of that was surely born of some latent insecurities. And part was a bit of arrogance and bravado I’d picked up from Dad, especially on these sorts of things. But a lot also seemed baked into the doctrine itself: after all, we Mormons believed we were members of God’s one true church, that these rules I was needled about had come from him and were essential for salvation, and that my family was one of the lucky few in the area who knew these truths.

It’s certainly possible for one to believe those things and to share them (even in the face of pointed opposition) with genuine love, humility, and confidence. I’ve known several who could do just that. But that would’ve required an understanding and maturity that was so far beyond me then.

Looking back, it’s curious to me how involved I was — how much the faith was a part of my life — and how little effort I made to figure things out for myself. I mostly just assumed it was all true. Genuine belief would follow, but not really back then. Ironically, the work just didn’t feel necessary, even though my beliefs were outside the mainstream of my peers. But my parents believed and had built their lives (and my life) around that belief. Their parents had built their lives around the faith, too. So had everyone I went to church and seminary with. Mormonism, it seems, was already such a prevalent, engrained part of my life that I think all that active participation felt synonymous with believing. And where I fell short (in some areas far short) of the ideal? The guilt only reinforced the correctness of the path; I was the thing that was flawed (though good luck getting me to acknowledge that to anyone back then, including myself).

I certainly have my share of regrets for those years. Mostly I wish I had been kinder. Not that I have many memories of being deliberately unkind, but I have wished (well before I stopped believing) that kindness would have been the hallmark of my budding faith — far more than clean language, sabbath day restrictions, or turning up my nose at Mountain Dew. There was certainly room for that theologically, but somehow it was rather lost on me and just not that important.

The truth is, though, if I really could go back now to that boy growing into a young man, if I really got to have some sort of "do over," this is what I'd wish for: that I could simply find a way to reassure that boy — over and over and over again, until he felt it in his bones — that he was "enough." That his accomplishments couldn’t add to that fact, nor his mistakes diminish it. Not even a little bit. [There may even have been room for that thought theologically, too, but you've got to strain to find evidence of it in Mormonism; even the notion of grace is seen by many in the faith as problematic, unless and until you earn it. So while I grew up singing that I was a "child of God," that message was almost meaningless to me (until my mid-30's); up until that point, it didn't seem to matter whose child I was unless I kept the commandments and did all the things. If anything, a noble heritage would damn me further if I fell short!].

It's hard to know what that teenage version of me might have looked like. Maybe that kind of emotional security would have left me less competitive and less accomplished, though not necessarily. Maybe I would've made even more mistakes, though I think it also would have put me in a better position to acknowledge them. . .and to learn from them. I bet, though, maybe more than anything else, a deep-rooted feeling that I was "enough" — and that everyone else was "enough," too — would have at least helped me be kinder.